In the breastfeeding world, people are categorized by how much milk they secrete.

If you make more than your baby needs, you’re an oversupplier. From the outside, one might think oversuppliers to be queens of the milky animal kindgom: abundant providers with chunky sweet cherubs. In reality, any oversupplier will tell you their condition is more of an affliction. Oversuppliers often struggle with clogged ducts and painful mastitis infections, babies that don’t gain weight because they’re filling up on less fatty “foremilk,” and the overwhelming constant need to relieve their painful swollen breasts. Yet, oversuppliers are often glorified in the viral videos our algorithms provide, featuring a mom pouring an obscene quantity (like 15 oz?!) of freshly pumped milk into a jar or bags for her fridge. Be careful what you wish for.

Then, you have the chronic undersuppliers, who unite in their struggles to make enough milk to feed baby and communally search for supplements that will magically make more milk flow. Its easy to sympathize with the worry of an undersupplier - and advertisers certainly have a field day selling supplements to this bunch. In an era when formula can quickly fill a feeding gap, undersupplying moms wish it was that simple. Because not every baby takes a bottle, formula is pricey, and babies with allergies, colic, or reflux often can’t drink typical formula - its trial and (t)error.

Just like the teenage cliques we may or may not have belonged to, breastfeeding moms belonging to the over- and undersupply camps tend to find each other and stick together. But this time, unlike in high school, the ingroups are usually beneficial.

It can feel lifesaving to find another mom with your same breastfeeding profile - someone with whom you can swap war stories, tactics, and certainly an equal share of laughter and tears. I don’t know about you, but I feel great honor when I get to check in on a new mom friend and share a genuinely helpful (and solicited) breastfeeding tip.

So why is regulating milk supply so hard? Shouldn’t milk supplied be a basic function of milk demanded?

The answer is yes. It should be that simple. Economics 101 tells us that supply should meet demand at market equilibrium. It also tells us, however, that supply and demand functions can be altered by market failures. And in milk making, market failures abound. For brief example:

You might be separated from your infant for any critical amount of time in the early days of their life, altering the potential demand for milk at the breast

Your baby (and you) may struggle to latch effectively, reducing effective milk removal and damaging your nipples, etc.

When our son was in the NICU, he had a 24-hour test done in which he could not be physically moved from his isolette or positioned to nurse on me. Those were 24 critical hours for him and me to learn to latch and establish supply. Our separation created a market failure.

During our son’s NICU stay I also had to learn to pump, using a hospital provided set of parts. The flanges didn’t fit right and I didn’t clean or sanitize them. (Don’t do this.) These and other factors led to me contracting mastitis, which majorly decreased my supply at a time when it should have been increasing. Another market failure.

As it turns out, making the right amount of milk is not as instinctually mammalian as one might expect.

Sources1

But wait — I’ve failed to mention one group of breastfeeders: the just enoughers. Just enoughers are those moms who make just enough milk for their baby to eat and grow, but don’t have any extra to build a freezer supply.2

In many ways, just enoughers are the lucky group, achieving the ideal of breastfeeding. These are the moms that get to watch their babies easily put on weight and drink to satisfaction without feeling overly engorged or needing to remove extra milk. As a newly minted member of this group, I can attest that my physical and mental wellbeing are exponentially improved in making just enough breastmilk, rather than too little (I was an undersupplier with my first).

Still, just as the grass is always greener on the other side, there are challenges to being a just enougher. Mainly, there is the struggle of running on empty without a freezer full of stashed milk. I pump 3x per workday to make enough milk for my daughter to drink the next day at daycare. I don’t make more than she needs, ever, so I don’t get a break. And the worry that I’ll run out whirs in the background of my mental hard drive without pause.

Recently, when I traveled over the course of a weekend without my daughter, I was wholly consumed with the refrigeration, storage, and transport of my freshly pumped milk at various hotels and through TSA. I couldn’t waste an ounce of what I made, as the small freezer stash back home wore down.

*A note on the freezer stash.

For so many moms, pumping and freezing breast milk is a lifeline. It offers freedom to go to a workout class or a girls’ brunch without baby, to return to work and send baby to a new care arrangement, or to [maybe even] quit pumping or nursing, while still having the supply to feed baby. Yes, the freezer is a great tool to ensure baby has a backup supply of milk. But it’s not always your friend.

The goal is not to feed the freezer, it’s to feed the baby.

As I see it, there is a risky tradeoff in worshiping at the altar of frozen milk, especially in the first six weeks of breastfeeding, when supply is just regulating. Focusing on pumping beyond baby’s nursing sessions to build up a freezer stash can create an oversupply, that will become a greater issue for both mom and baby in the long run. Remember the oversupply issues I mentioned earlier: poor fat content in milk, risk of engorgement, clogs, and The Dread Pirate Mastitis, to name a few.

But for moms returning to work and separating from baby after mere weeks, what’s the viable alternative? You really are damned if you do (pump extra milk) and damned if you don’t.

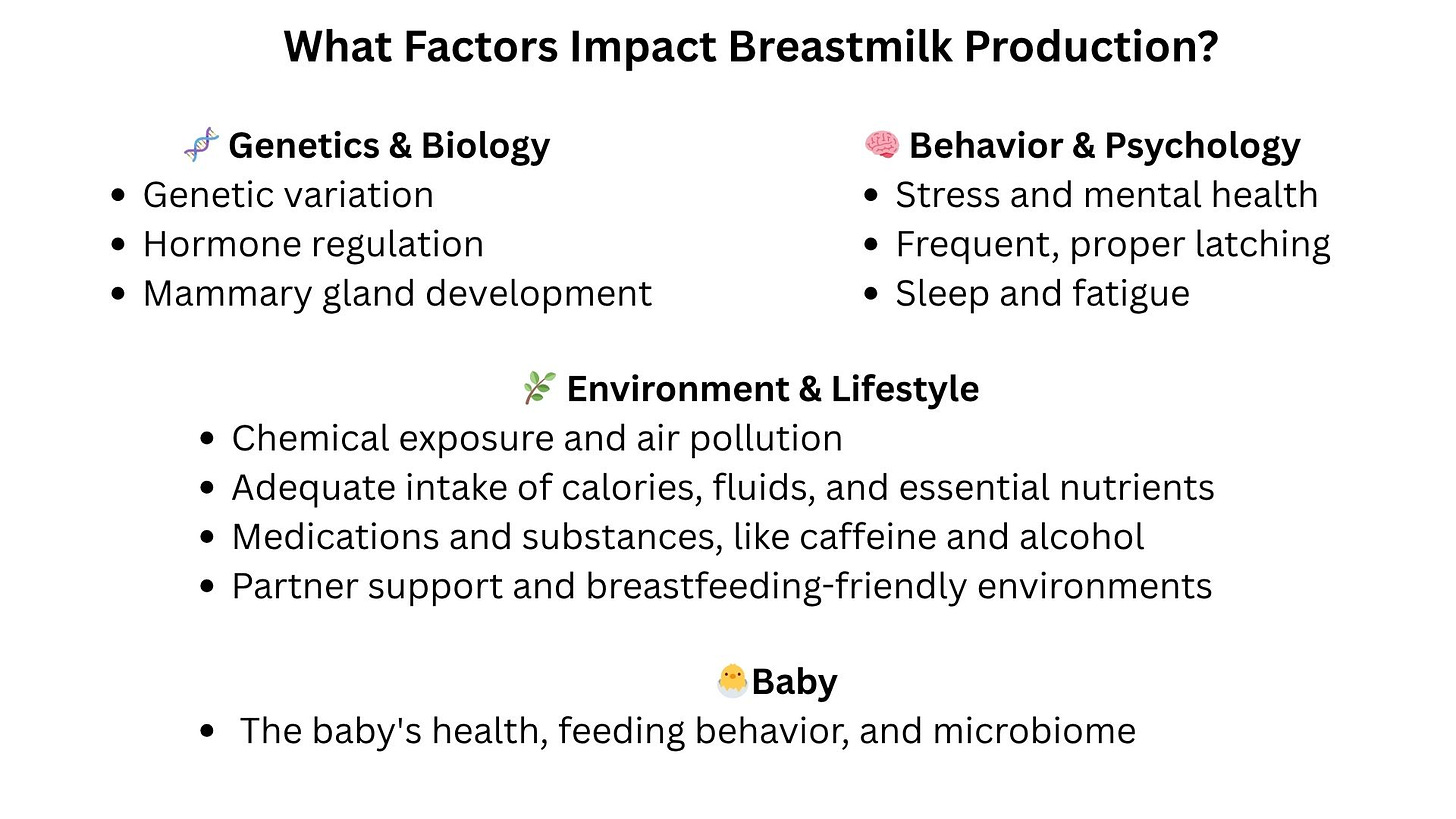

I wish I could say it was all lessons learned from baby #1 that led me to upgrade my undersupplier status to just enougher with baby #2, but let me emphasize that my own behavior was just a part of the equation. Circumstance and biology make up a lion’s share of the change:

First, let’s explore the biology: After breastfeeding each individual baby, a breastfeeder’s mammary glands have an epigenetic memory, making milk come in faster and more abundantly for second babies. Put simply, second-time breastfeeding moms can achieve a better supply more quickly.3

Second, the circumstance: Compared to our son’s rocky start, our daughter spent no time in the NICU, latched willingly, and generally was more patient at the boob, making it more possible to learn how to latch together over time (this was still a huge challenge for us.)

Finally, what I controlled:

Primarily latching our daughter, rather than pumping to establish my supply, paid off in a big way. I was able to keep my breasts healthy (babies are better at removing milk than pumps and exclusively nursing lowers the risk of mastitis), and I found that 8 nursing sessions per day made for a full baby tummy and a good milk removal cadence to prevent engorgement.

I did ultimately need to build a small freezer stash, but I waited to do this. At the advice of my lactation consultant, in the very last weeks of my parental leave, I added just one 10-minute pumping session per day at the same time each morning, until I had about 2-3 days worth of milk stored up. The sacrifices I made here were substantial. Without stored breastmilk or formula in use, I was attached at the hip to my daughter, day and night. It was a big investment into her health and my own breastfeeding health - one I’m still paying for in sleep debt. But she and I are so incredibly bonded and I wouldn’t trade that time for anything.

Bonus — things I could still do better: I still struggle to get enough nutritious calories and sleep, while breastfeeding. Chalk it up to the toddler, the disruptive cat, and our daughter’s cow’s milk allergy that prevents me from snacking and filling up on lots of my favorite fatty foods. I end up lightheaded, starving, and excessively thirsty a lot of the time.

How can exclusive pumpers regulate supply to become just enoughers?

To be honest, this feels really tricky to me, as someone who did not succeed in establishing enough supply as an exclusive pumper with my first. But, is it possible? Absolutely. We know that regular pumping is critical to stimulate demand and build supply. That part is straightforward. But, I think the primary objective for exclusive pumpers to avoid an oversupply should be to pump the quantity of milk that your baby finishes in a bottle, not more.

Other critical tools to establishing supply via pump include:

fitting your flanges with precision,

making sure your breasts truly feel empty after each pump,

pumping every 2-3 hours round the clock until your supply is established, and

taking great care to prevent clogged ducts (sunflower lecithin, motrin, and milk removal help me when I feel a clog forming)

I’ll end, as usual, with an invitation. I’d love to know your experiences with building your milk supply. For those oversuppliers, how have you managed that excess supply over time? Anything you would have done differently? Any tips you would give to a new mom dealing with an oversupply? This is the one arena I have yet to navigate in breastfeeding and I know it can be so tough!

—LJ

Thanks for reading! If you have thoughts or suggestions for me to improve the publication, please share them. And if you’d like to support Motherloud, the best ways to do that right now are below:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK148970/?utm_source=chatgpt.com

https://ajcn.nutrition.org/article/S0002-9165%2823%2901560-5/fulltext?utm_source=chatgpt.com

https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/17/6/1093?utm_source=chatgpt.com

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-024-57158-z?utm_source=chatgpt.com

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5005964/?utm_source=chatgpt.com

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0002916523015642?utm_source=chatgpt.com

Freezing breastmilk is of prime concern to newly postpartum American moms because without paid leave standards, our children are more likely to be separated from us for long stretches of their days when they are very little and very much still relying on our milk for their nutrition.

https://newsinhealth.nih.gov/2015/07/milk-gland-remembers-past-pregnancy